Cleaning & Conservation

The University Art Gallery (UAG) cares for a permanent collection of about 3,000 art and historical objects from various cultures and periods. Valuable holdings in American painting, old master drawings, and Asian prints and scrolls make our collection a significant educational tool for students and the community at large.

Serving as an immersive laboratory for the arts, the UAG focuses on experiential learning. Objects from the collection are used for many educational purposes, including the Museum Studies minor, undergraduate and graduate gallery internships, and independent research.

As part of its stewardship of the collection, the UAG faces the important challenge of caring for the art entrusted to us. We are dedicated to preventive care and we take necessary precautions when handling and exhibiting artworks. The UAG took an important first step in the summer 2013 by securing a grant from Heritage Preservation’s Conservation Assessment Program (CAP), which provided a general conservation assessment of the gallery’s collections. Wendy Bennett, a professional paper conservator, spent two days surveying the site with the UAG curator Isabelle Chartier; she evaluated the gallery’s current collections policies, procedures, and environmental conditions (more on the CAP here). Assessments for particular objects in the collection were also conducted over the last year to help us find ways to care for paintings, works on paper, and sculpture.

You can help us preserve our artistic and historic heritage by clicking here. Your donation will be used for restoration and preventive conservation of artworks and for related educational projects overseen by the UAG.

Below are various examples of conservation projects to which you can contribute. Conservation treatments will become part of the educational training the gallery is dedicated to offer to students.

For questions, contact the curator, Isabelle Chartier, or 412-648-2423. We thank you for your support!

Previous Restorations

Preventive Conservation

Restoration

Previous Restorations

The Nicholas Lochoff Paintings in the Cloister

The Frick Fine Arts Building is one of the University’s most prized places on campus. It houses the magnificent paintings by Nicholas Lochoff. These to-scale replicas of masterpieces from the early Italian Renaissance, a gift from Helen Clay Frick, were installed in the cloister upon completion of the building in 1965.

From 1911 until his death in 1945, Nicholas Lochoff worked meticulously to recreate faithfully the Italian masters’ techniques and styles. He studied the color pigments of the original paintings and experimented with materials used in the 14th and 15th centuries. Something of a pioneer in the field of conservation, Lochoff spoke out against the frequently inadequate practices of repainting and retouching of original works that prevailed during his time. Instead, he pursued his own means of preserving these masterworks of the past by making carefully researched renderings of them: he argued that if anything were to happen to the originals, his copies would remain for future generations to admire. As part of his mission to educate the public about art and its proper care, he also sometimes painted two versions of the same work: one that recreated the artwork in its 20th century condition, cracked and darkened, and another as he thought the painting might have looked when the artist completed it. Without ever touching the originals, Lochoff thus ingeniously “restored” artworks to their original state.

Over time, Lochoff’s masterwork copies in the cloister of the Frick Fine Arts Building suffered from environmental conditions, mainly sunlight and humidity. In 1999, guard rails and plexiglass covers were installed to protect the works from further damage. Some of the paintings were also cleaned and restored at that time by conservator Christine Daulton.

Click on the links below to learn more about the Lochoff restoration project. As part of its educational programs, the UAG will offer guided tours of the cloister beginning in Fall 2013. Schedules will be posted on the UAG Facebook page and website.

Take a tour of the Cloister on WQED

See the story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

George Hetzel Painting

George Hetzel (1826-1899) is among the prominent artists of Western Pennsylvania in the 19th century. Born in a small village in Alsace, France, his family moved to America in 1828 and settled on a small farm land in Allegheny City, now the North Shore of Pittsburgh.

Hetzel trained at the Düsseldorf Art Academy between 1847 and 1849. He returned to Pittsburgh where he became a respected artist and received commissions to paint still lifes, portraits and landscapes. The artist is probably best known for leading a group of students and painters that would become known as the Scalp Level Artists. Named from the area near Johnstown, at the confluence of Paint and Little Paint Creeks, this group of men and women captured Western Pennsylvania’s diverse landscape by painting directly from nature, en plein air.

In storage since the 1960s, this beautiful Hetzel landscape and its frame had suffered damage that demanded restoration. In 2005, conservator Christine Daulton cleaned and restored the painting. On her conservation report, she explains how she repaired a large tear in the upper left quadrant and consolidated numerous losses and flaking on the surface, especially along the bottom right edge, probably caused by water damage.

Previous restorations on the painting were visible and determined inadequate. Christine Daulton writes: “The sky had been completely overpainted, and this overpaint covered the edges of the trees, giving them a squared-off appearance” - uncharacteristic of Hetzel’s style. However, the removal of this overpaint proved to be unsuccessful: the paint being lead-based, its removal would have damaged the underlying original paint.

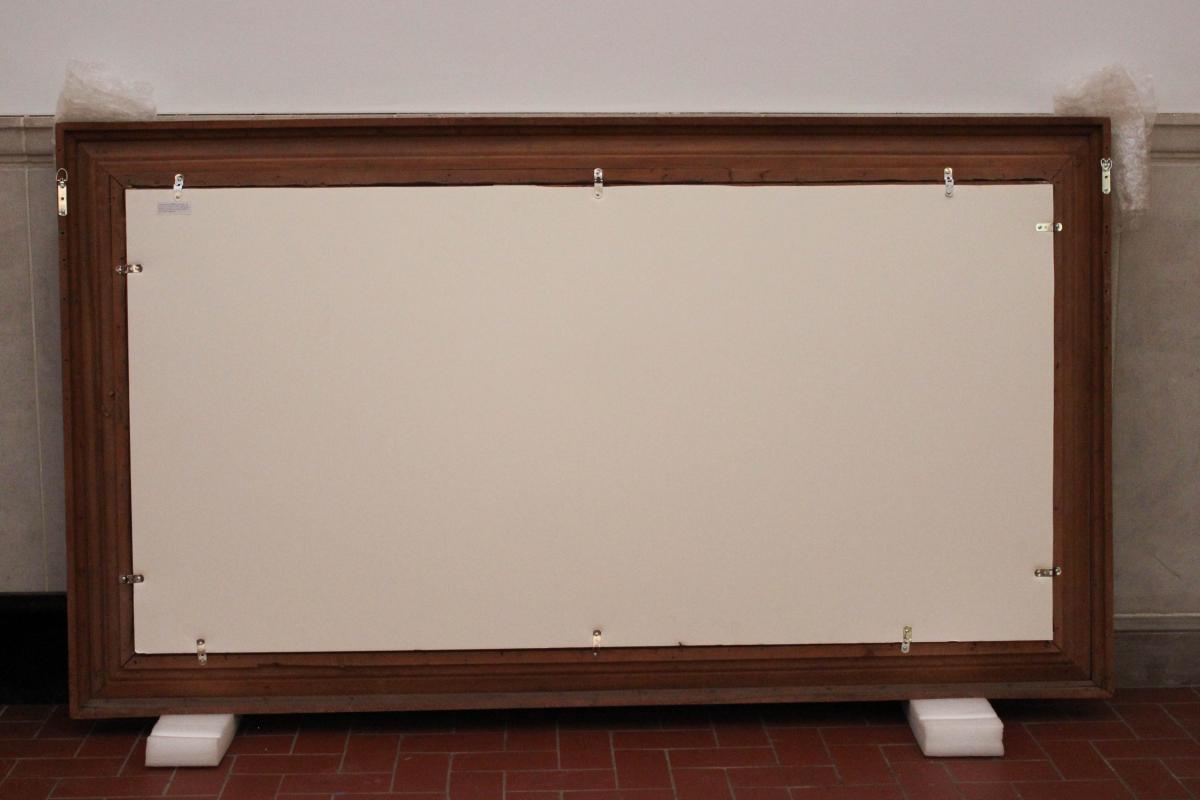

The conservator removed the dirt on the surface with distilled water, as well as the old varnish, using an organic solvent. The tear was mended, and the painting was fully lined with polyester sailcloth. A protective backing board was added to the back of the painting, and it was reframed with a protective glass.

This painting is on view in the exhibition Rediscover: The Collection Revealed, from September 6th to October 19th, 2013.

Preventive conservation

The American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC) defines preventive conservation as follows: “Preventive Conservation is the mitigation of deterioration and damage to cultural property through the formulation and implementation of policies and procedures”. Before resorting to restoration treatments, adopting proper measures to prevent and minimize damages is the safest and most cost-effective option. Such measures include environmental controls (temperature and humidity), protocols for storage, handling, exhibition and transport, as well as collection policies and emergency preparedness plans.

Exhibitions

As we prepare exhibitions, we make sure the paintings are in stable condition. We turn to the expertise of professional framers and art handlers to stabilize paintings in their frames. Acidic tapes and boards, as well as metal wires can cause damage to canvases. This is why old backing boards are carefully removed and replaced with acid-free foam boards, keeping the dust from accumulating on the back of the canvas. The interior of the frame is lined with acid-free barrier tape or felt to protect the surface of the canvas from rubbing onto the wood. Old wires are removed and D-rings, placed on both sides of the frame, are used to hang the painting securely on the wall.

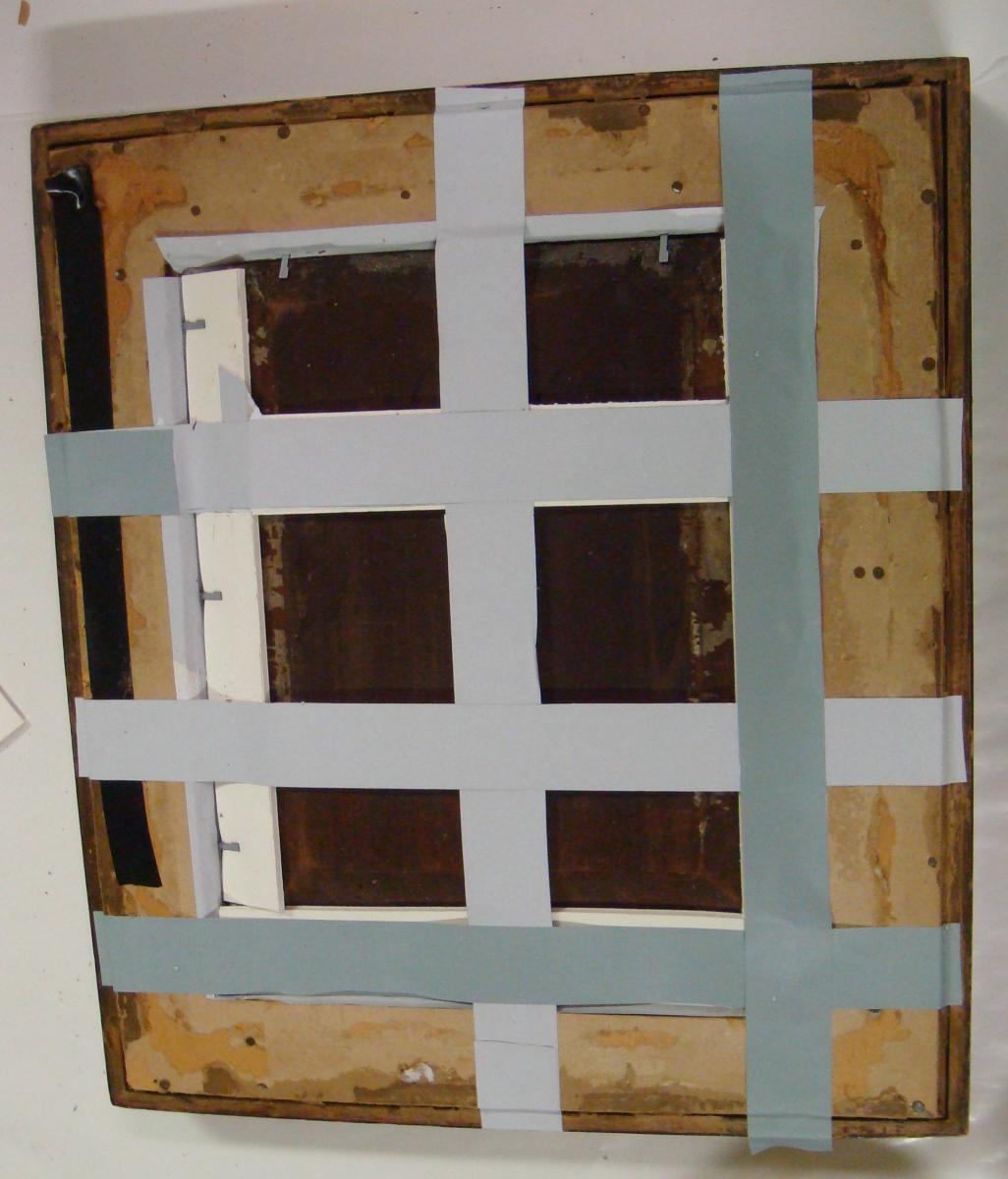

Briget Shields is replacing this old acidic backing from the frame before it is put on display. The backing is important: it buffers the relative humidity fluctuations, keeps dust and debris from infiltrating between the lower stretcher and the canvas, and protects the painting from damage from the back.

This small 19th century portrait of James Mountain, former President of the Pittsburgh Academy, by artist Francis Cézeron, was framed with an old frame and mat, probably original to the painting. The wooden mat was scratching the surface of the painting, causing losses of paint. During installation of the 2012 exhibition Faces to Names, Briget Shields reframed the painting, covering the inside of the oval mat with archival barrier tape. The portrait, painted on wood, was placed back in its original frame, and acid-free strips were inserted to ensure stability of the wood panel.

Before exhibiting paintings, we make sure to replace the old hardware and add acid-free backings to protect the paintings.

The old tape and acidic paper is scratched off from the back of the frame. The interior of the frame is lined before placing the painting back in its frame. Nails originally used to hold the canvas in the frame were protruding from the wood; they would risk scratching and puncturing the canvas. Z-clips now stabilize the stretcher within the frame.

Storage

Each year, the UAG assesses its storage needs and invests in archival materials: interleaving paper and Solander boxes for works on paper, archival boxes, ethafoam or Nomex wrap for delicate 3D objects. Gallery interns are trained to safely handle objects, paintings and works on paper, and learn best care practices when storing or exhibiting the collections.

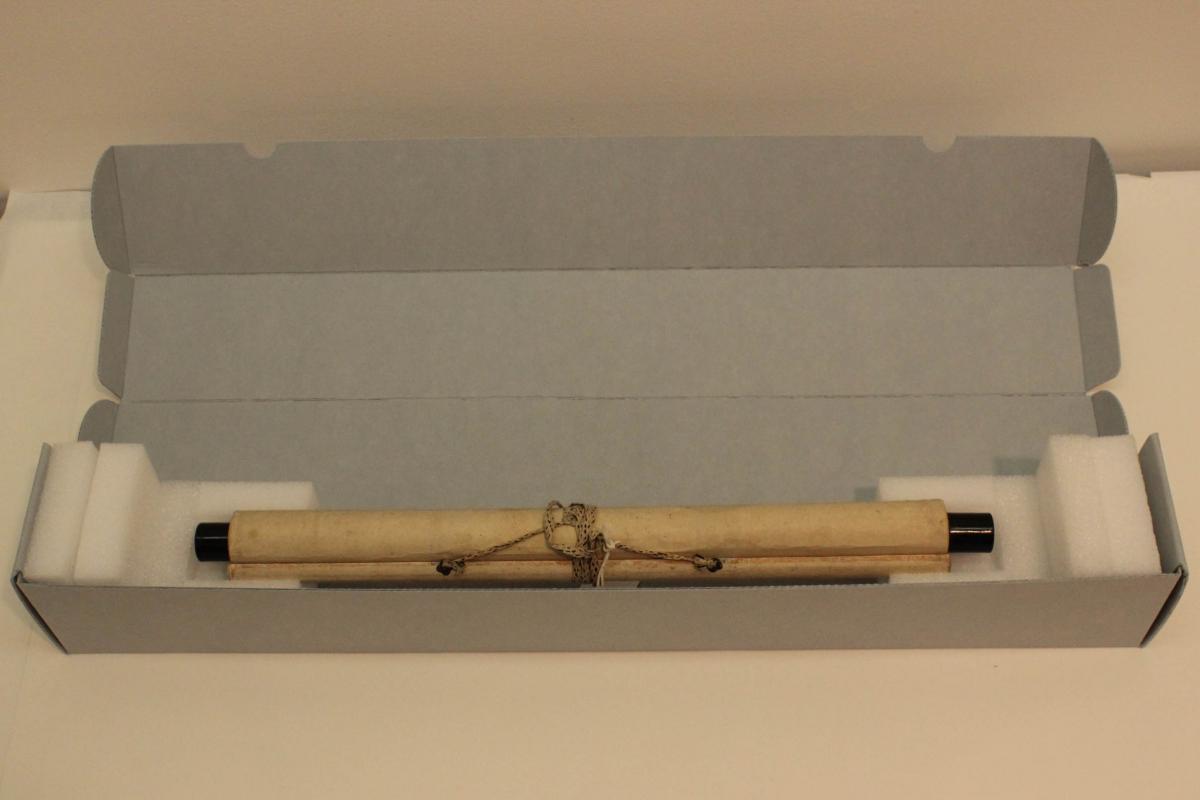

Scrolls are stored in acid-free B-flute corrugated boxes with inert polyethylene foam cradles, allowing the scroll to "float" inside the box. This eliminates pressure on rolled materials. The box protects the object from light and dust while serving as a buffer from climatic fluctuations.

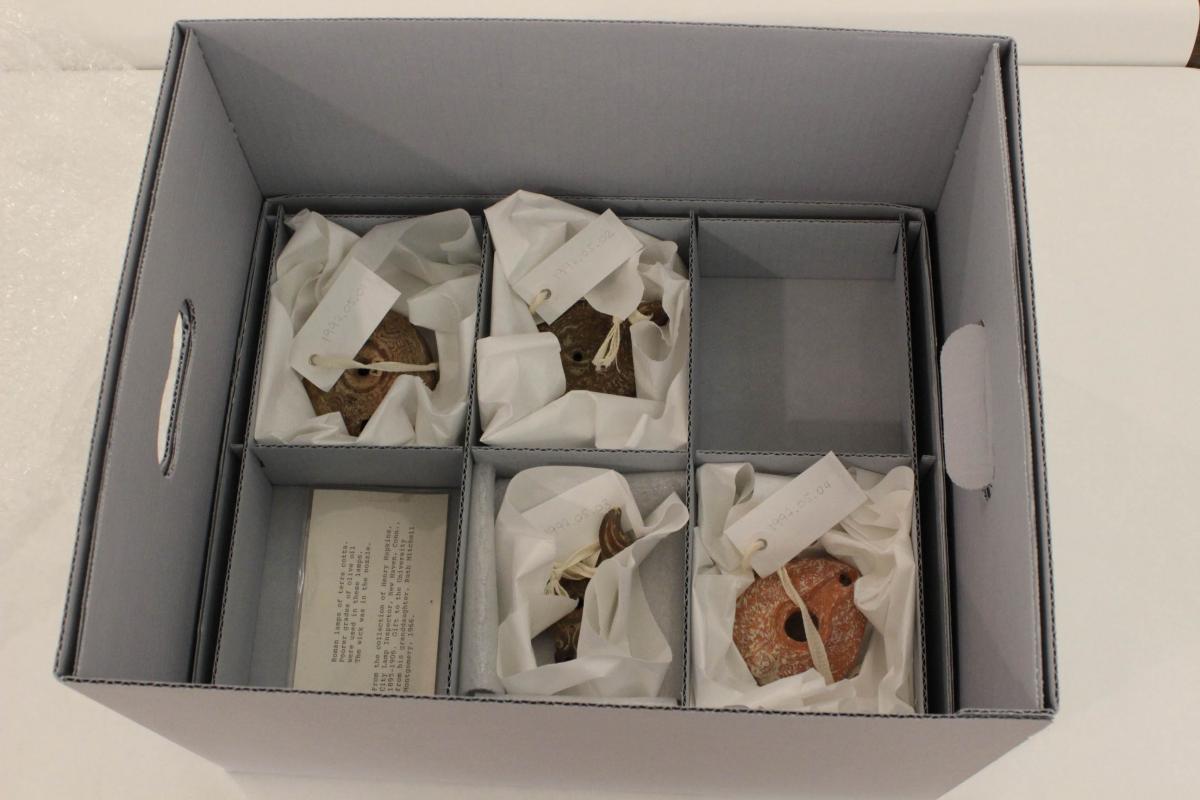

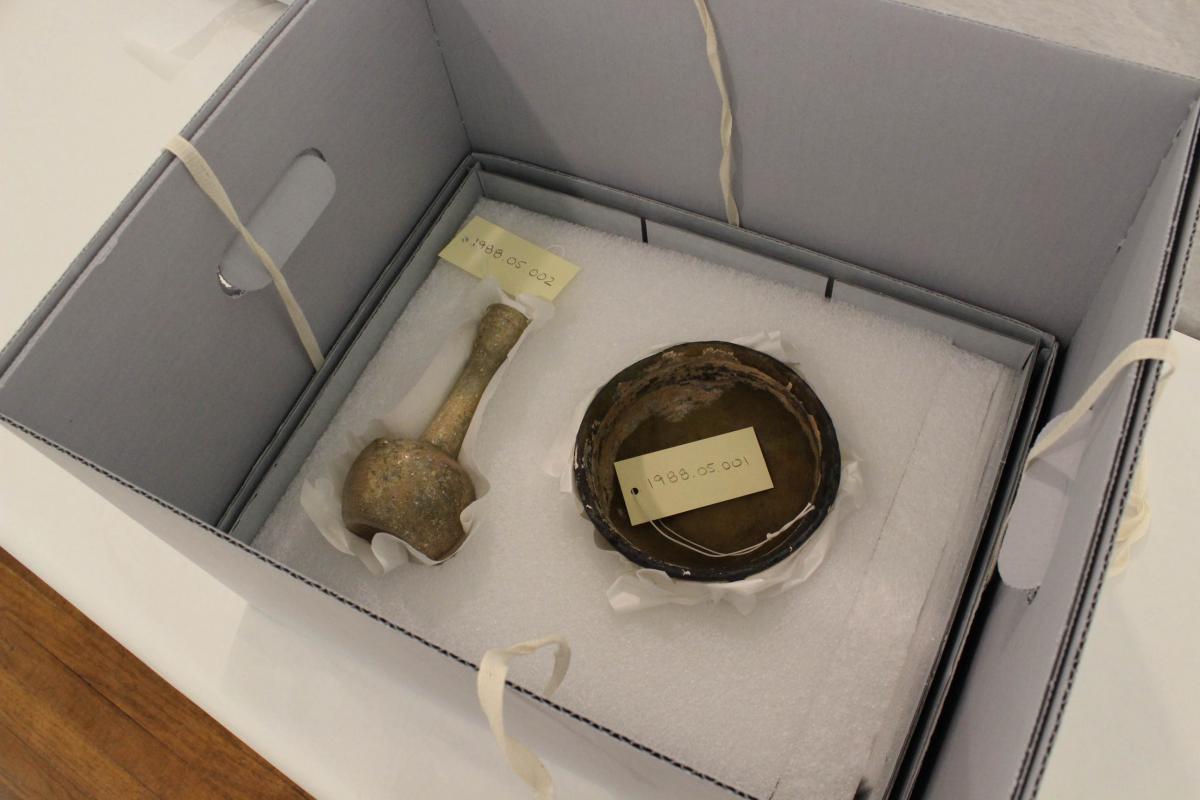

Removed from their previous packaging, these Roman lamps and glass containers from the 1st century BCE were transferred into acid-free B-flute corrugated boxes and trays. Ethafoam, molded to the size and shape of the artifact, and Nomex wrap, are used to keep the object in place and protect it from potential shocks and vibrations, light, dust and climatic variations.

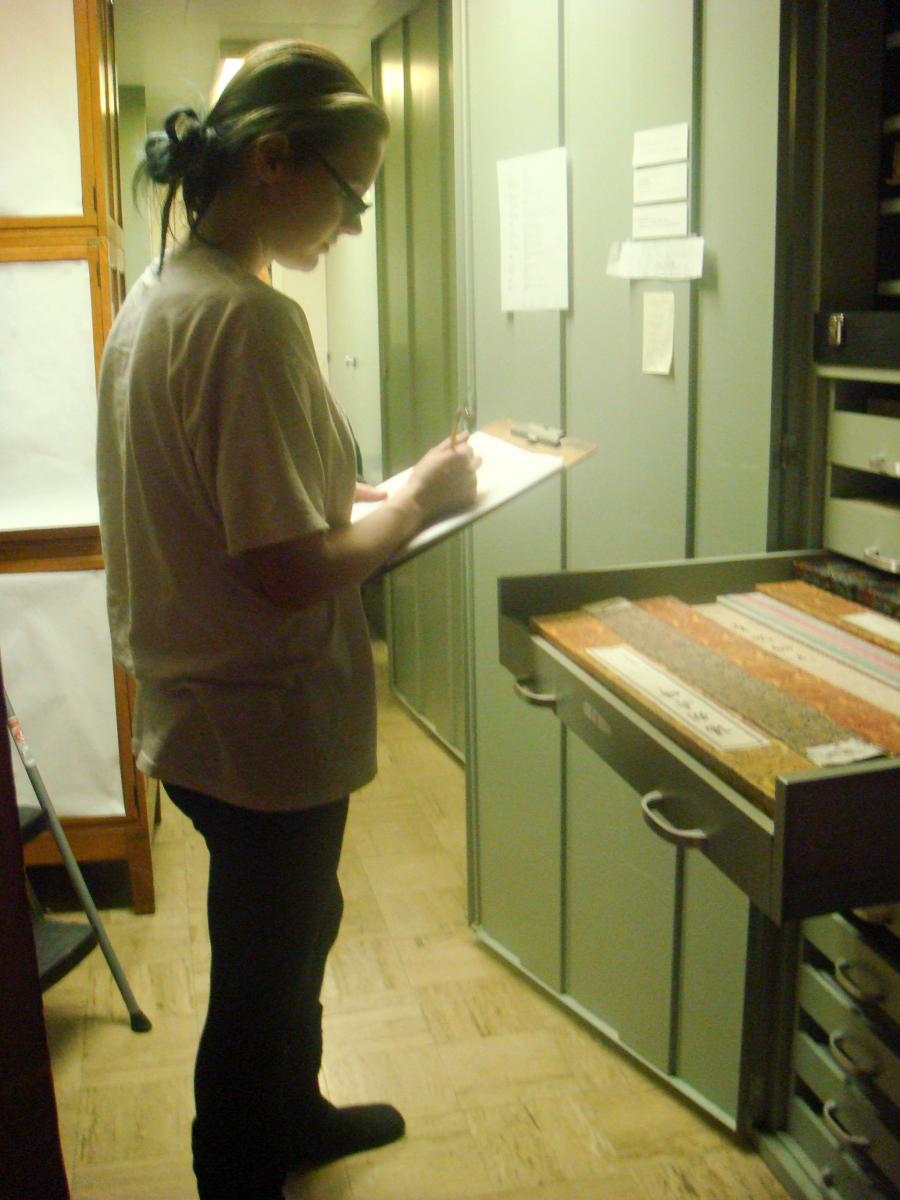

Working directly with the curator, interns are trained to handle artistic and historical artifacts and apply best care practices when working with collections.

Jamie Fredrick, a gallery intern in 2013, is inventorying the scrolls in the collection and assessing storage needs.

Arlene Mehelich, a gallery intern in 2013, is interleaving these works on paper with acid-free and lignin-free tissues. She writes the object ID in pencil on the outside of the folder for easier identification.

Restoration

Foerster Family Portrait and Frame

Emil Foerster (German/American, 1822-1906), Portrait of the Foerster Family, c. 1856, Canvas mounted on board, 1980.11

Emil Foerster’s portrait of his immediate family stands out as his most ambitious work in the collection. The individual character of each family member is telling of the time Foerster invested in the portrait. Though the family connects through subtle hand gestures, each person maintains their own presence and relationship with the viewer. In this way Foerster captures the complex dynamic of a first generation German family in Pittsburgh. Portrayed are his mother, (seated on the right), father (center), and siblings John, Edward, Charles, Joseph, Albertina and the youngest, Eliza. The artist confidently poses third from the left between his brother Edward and father Dr. Martin Foerster and gazes introspectively past the viewer.

The family portrait was likely painted at Foerster’s first Pittsburgh studio on Lowie Street in Troy Hill. However, the artist spent the majority of his career working from his 5th Avenue home and studio across from what eventually became the Cathedral of Learning. Foerster studied painting in Dusseldorf, Germany before following his parents and siblings to Pennsylvania. Once in Pittsburgh, Foerster had a productive career and painted portraits of several prominent Pittsburgh figures including Captain and Mary Schenley.

The University of Pittsburgh celebrated the donation of the Foerster Family Portrait alongside several other Foerster works in 1933 by his granddaughter, Mrs. Elsa Foerster Michael. These works originally hung in the Cathedral of Learning as exemplars of Pittsburgh’s artistic community and as a celebration of the city’s diverse heritage. Two other portraits, a sketchbook, and the artist’s palette in the University Art Gallery collection allow us to see the materials and artistic process of a once well-known artist.

Exactly 80 years after it was donated to the University of Pittsburgh, the Foerster family portrait requires the care of conservators. The canvas shows signs of relining and previous restorations. The goal of the restoration is to remove the plywood board on which the canvas is mounted, repair small canvas tears, and re-stretch the canvas onto wood stretchers. The surface varnish, which has caused the painting to yellow, will be removed, revealing the Foerster’s original subtle coloring, and allowing darker details to come through and which are difficult to see in its present state. Places of minor paint loss will be retouched.

The goal of the restoration is not to erase the painting’s 160 years of age, but to restore and stabilize it in order to make it accessible to students and the public and to prevent future damage to such an important piece of Pittsburgh’s heritage.

Foerster’s family portrait belongs with its original 19th century solid wood carved gilded frame. In order to unite the two, the frame needs to receive the care of a frame conservator who will clean and repair the frame, and stabilize it to prevent future damage.

A professional assessment was conducted by conservator Emily Cohen in June 2013. The painting was further assessed by conservator Rikke Foulke in August 2013. Details are below.

Frame

Description: Mid- to late-19th century American gilt frame with geometric foliate style ornament on the outside edge, followed by reverse ogee curve leading to bamboo style pattern on highpoint – egg and dart with ¼” cove edge, center large cove with highly textured surface that is rougher than fine sand usually found on such styles: 1” round edged by floral ornament on inner liner with 3/8” cove. Each corner had a large flower with 3 pistil and stamens surrounded by 4 leaves with two smaller flowers with leaves above it on the uppermost section. Only one corner remains intact. The entire frame was gilded both on the front and sides. The two half-round highpoints were silver with tinted shellac to make them appear gold in color. It appears the rest of the frame was done in 22-k gold.

Overall condition: Structurally, the frame is solid, but the surface has suffered a lot. It is missing ornamentation, and has suffered flaking and cracking. This frame has extensive surface losses particularly on the bottom rail and in the large cove. All 4 corner ornaments are missing various sections along with sections on the outer edge. The piece has suffered either from being in a fire, with extensive water damage and/or in high humidity over a long period of time. The gesso continues to flake and crumble off from the substrate and will continue to do so until restoration starts.

Proposed treatment: Surface preparation and cleaning, gesso replacement, cast/carve and replace missing ornament losses, in-gilding and new gilding with 22-k gold, toning to match cleaned but existing finish. Install painting and cleats for hanging.

Priority: This frame and its painting are of high priority for the gallery. Without restoration, the piece cannot be displayed to the public. The longer it waits, the more likely it is to suffer more flaking and cracking. It is a valuable piece and an important example of 19th century American art, especially in the Pittsburgh area. We are fortunate that the frame is still solid. This is a unique piece, and the moldings and metal pistils in the corners are rare ornaments.

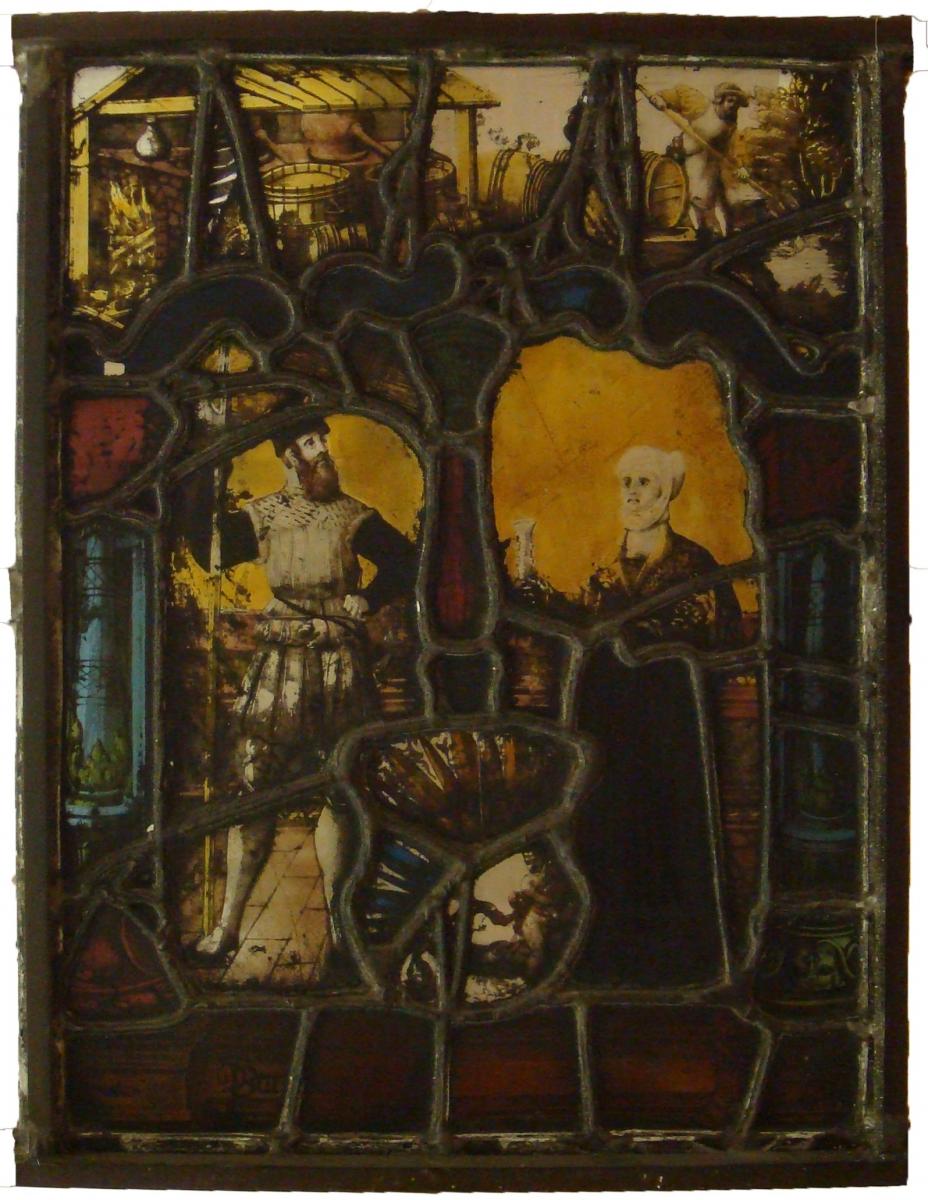

Stained Glass Panels

The University Art Gallery owns 15 Northern European stained glass medallions dated from the 15th and 16th centuries. These medallions are certainly unique in Pittsburgh. They were transferred from the Department of Fine Arts on the 7th floor of the Cathedral of Learning to the Frick Fine Arts Building in 1965. Exhibited in 1979 in the UAG, these panels have attracted attention from the scholarly community, among whom the American Committee of the International Corpus Vitrearum.

The roundel entitled “Joseph sold to the Ishmaelites,” dated ca. 1480-1490, was loaned for an exhibition at the Metropolitan Cloisters in New York in 1995. The conservation department at the MET oversaw its restoration, which consisted of removing the clear glass and lead bars around the roundel. The UAG would like to proceed with a similar conservation treatment for the other panels, some of which were published in Studies in the History of Art journal in 1985.

Description: The medallions are mounted on lead bars and clear glass. These mounts appear to have been added in the 20th century.

Condition: The medieval medallions are intact, although the clear glass that surrounds them is in many cases cracked and broken. The medallions are currently stored in heavy wooden crates, inadequate for such fragile objects: there are two panels per crate and no protective foam or padding to protect the glass. The heavy crates do not have any handles or casters to facilitate handling, making it difficult for UAG staff to move them without putting the objects at risk of breaking. The medallions and their mounts do not fit in cabinets or drawer units and there is no other adequate space for the crates in which they currently reside in the storage rooms.

Proposal from Hunt Stained Glass Studios, Inc.

- Remove / dispose of glass and lead surrounding intricate medallions

- Cut bronze bars on the outside of the medallions

- Drill holes in bronze bars or add eyelets for hanging

This procedure would allow the UAG to safely store the medallions and make them available for public display.

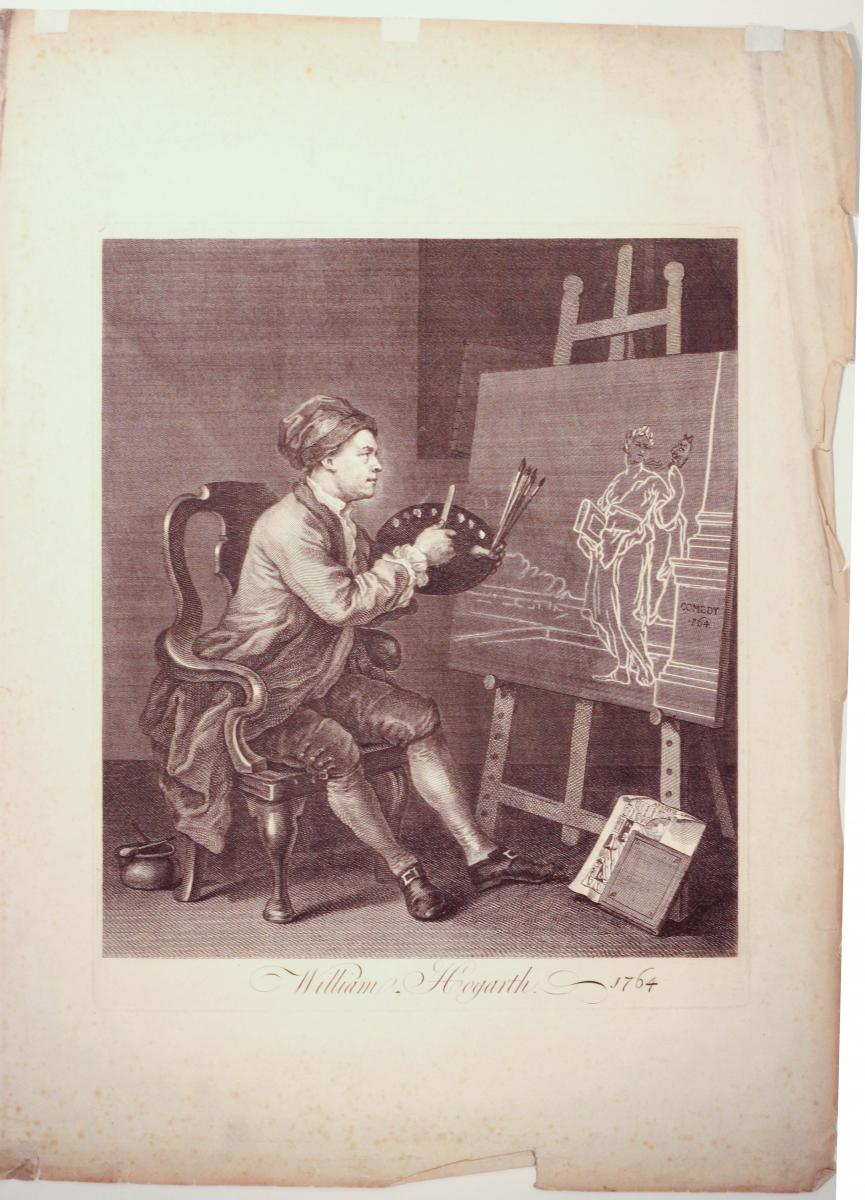

Works on Paper

Katie Napolitano (front) and Siqiao Lu (back), gallery interns in 2012, are inventorying works on paper and storing them carefully in Solander boxes, using acid-free interleaving paper between each print.

As part of its internship program, the UAG has been re-housing works on paper in the storage room and testing for acidity in the current mats. Although we now use exclusively archival materials and acid-free interleaving paper, it was determined that nearly 75% of the works on paper (about 1,000 in the collection) are either matted with acidic mats or in need of restoration treatment.

Acidic mats threaten the stability and appreciation of old mater prints and drawings. This is why the UAG is seeking to remove all acidic mats, a crucial action to avoid irreversible effects, irremediable loss and more costly treatments in the future.

Works on paper constitute a large part of our research and educational programs. For safe examination and handling of prints, drawings and photographs, we need to replace old mats with new museum-quality mats.

This matting project will have educational implications. Through the Department of Art History and Architecture, students will be involved in each step, as part of undergraduate internships and/or graduate teaching assistantships. Furthermore, the project will engage with the new interdisciplinary Museum Studies minor sponsored by the HAA Department. Students from various programs who enroll in the minor will receive practical experience in preventive conservation and museum storage standards, as well as a theoretical understanding of the issues involved, allowing them to develop professional skills and acquire essential tools for today’s job market.

This project will contribute to the care and preservation of a historically significant collection, and maintain these works for future generations of scholars and the public to enjoy.

Work Methodology

The prints will be divided into the following groups:

- Drawings

- American prints

- European prints

- Asian prints and scrolls

- Modern/contemporary prints

Prints from each of these groups will be placed within two categories:

- No matting required

- Matting required

The paper conservator will examine prints from each group and determine:

- Objects that can be matted as is: these are prints that are currently un-matted and that do not need conservation work.

- Objects to be prepared for re-matting by the conservator: these prints are in good condition but are matted with acidic mats. Adhesive hinges can only be removed by the paper conservator to avoid tears to the paper. Prints that can be un-hinged on-site will be added to category 1.

- Objects that need conservation treatment: these prints need special attention to remove the hinges and/or are unstable. The prints that will receive conservation treatment will be selected according to their vulnerability and value; they show signs of deterioration (tears, mold, transfers, stains, etc.), which affect the appreciation of the print, restricting it from being used in exhibitions or studied by scholars.

- Objects that can be stored in a storage folder: these prints, usually of larger sizes, are un-matted and show no sign of vulnerability; they do not need conservation treatment and can remain un-matted.

Benefits for the collection

- Saves the prints from deteriorating and being marked by acid burns

- Allows a safer storage in Solander boxes

- Allows easier handling while examining and studying the prints

- Allows easier and less costly framing for exhibitions, because the mats have a standard size

Student involvement

- Assessing the print collection and testing for acidity of the mats

- Help in classification of objects to be restored, un-matted and re-matted

- Enter conditions and new locations of the prints in the database

- Help in hinging the prints to their new mats and adding interleaving tissue in each mat

Thank you for your support of the UAG’s permanent collection. More details are available on our University Art Gallery Tumblr blog. You can also follow us on Facebook, University Art Gallery – University of Pittsburgh.